Authors

John Hartig, University of Windsor, Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, jhhartig@uwindsor.caCollin Knauss, University of Michigan - School for Environment and Sustainability, crknauss@umich.edu

Background

The Detroit River has long served the United States and Canada as a critical transportation corridor and industrial hub that helped shape the economies of the shared metropolitan region (USFWS 2005). By 1950, the city of Detroit became the fifth largest city in the U.S. and the river helped Detroit emerge as the nation’s auto-manufacturing leader, primary shipping channel, and industrial epicenter in the U.S. However, the ecosystems of the Detroit River and western Lake Erie suffered tremendously from the extensive human modifications, pollution, and development. The development led to urbanization, industrialization, and channelization of the river that resulted in severe pollution and ecological degradation. For decades, the connecting channels in the Great Lakes, including the Detroit River, collected industrial and municipal effluents that deteriorated water quality and degraded the river’s diverse habitats (EC & EPA 1988, Hartig and Thomas 1988).

Detroit’s industrial expansion and population growth reached a tipping point in the 1960s, when the Detroit River was considered one of the most polluted rivers in North America (Hartig and Wallace 2015, Manny and Kenaga 1991). Damaging environmental catastrophes, including the Rouge River (Detroit River’s major tributary) catching fire in 1969 due to oil pollution, widespread waterfowl kills from oil, contamination by toxic substances like PCBs and DDT, and discharges of raw sewage, contributed to deteriorating ecosystem health and its designation as an international pollution hot spot or “Area of Concern” (Hartig and Wallace 2015). Figure 1 shows an oil spill from the Rouge River entering the Detroit River in 1966.

Figure 1. Water pollution of the Detroit River, 1966 (photo credit: Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

The long-standing view of the Detroit River as a working river that primarily supported commerce, industry, and technological progress, began to shift after the 1960s with the public becoming increasingly engaged in addressing the river’s health (Hartig and Wallace 2015). Spurred by legislative and public engagement initiatives, 40 years of pollution prevention and control resulted in substantial environmental progress since the 1960s (Hartig 2014). This remarkable turnaround for the Detroit River continues today, with increased ecological recovery, economic revival, and community pride for the river (Hartig et al. 2010). These recent successes also prepared the region for the creation of the Detroit International Wildlife Refuge (DRIWR), the first and thus far only international wildlife refuge in North America (Hartig and Wallace 2015).

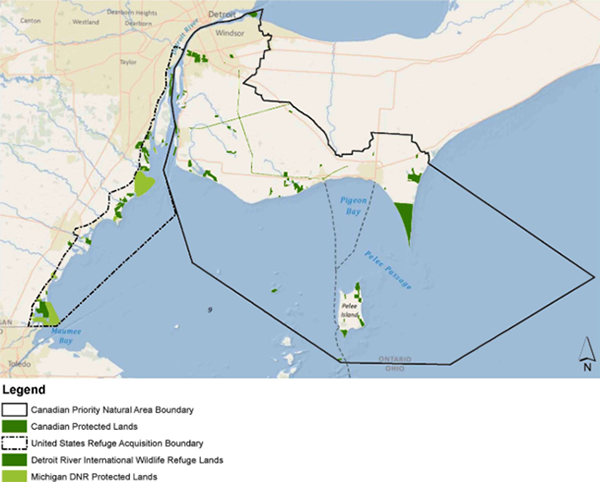

In 2000, a group of U.S. and Canadian conservationists and scientists developed a conservation vision for the lower Detroit River ecosystems, promoting the establishment of an international wildlife refuge. Soon after in 2001, the refuge was established on the U.S. side by Public Law 107-91, with primary management and oversight by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Canada later created the Western Lake Erie Watersheds Priority Natural Area, overseen by the Essex Region Conservation Authority (ERCA), to coordinate amongst Canadian federal, provincial, local, and nongovernmental organizations, and work with U.S. partners in fulfillment of the international wildlife refuge (Hartig and Wallace 2015). The boundaries of these two complementary and reinforcing initiatives were designed to fulfil the spirit and intent of the DRIWR and are presented in Figure 2. The region’s exceptional biodiversity is recognized in the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, the Western Hemispheric Shorebird Reserve Network, and the Canada-U.S. Biodiversity Investment Area Program (Hartig and Wallace 2015). In addition, the DRIWR’s location is unique because it is one of only a few refuges to exist within a major metropolitan area (Hartig et al. 2010).

Figure 2. U.S. refuge acquisition boundary and Canadian Western Lake Erie Watersheds (Hartig and Wallace 2015).

Status and Trends

Protecting and conserving the remaining critical wildlife habitats in and around the DRIWR represents a high priority for the USFWS and its many partners. In 2005, after several years of coordinated public-private planning, the USFWS completed the Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) for the DRIWR. The CCP initially defined the DRIWR’s strategies for fulfilling its legal purpose, management goals for a 15-year period up to 2020, and specific objectives needed to accomplish the goals. To accomplish the management goals, agencies and stakeholders engaged in cooperative management that has enabled the DRIWR to develop robust partnerships and expand its conservation area through agreements with industries, government agencies and other organizations (Hartig et al. 2010).

The DRIWR’s long-term goal is to protect and restore sufficient habitat for a healthy ecosystem that can support desired fish and wildlife populations and diversity. In the short-term, coordinated efforts have aimed to protect the remaining relatively healthy headwaters, biotic refugia, riparian habitat, and floodplains (Hartig et al. 2010). Once protected, agencies have recognized the importance of restoring connecting corridors between healthy habitats to link them together (Hartig et al. 2010). Often, these complex restoration projects have required cooperation and many levels. The primary leadership for expanding and managing the DRIWR on the U.S. and Canadian sites has been the USFWS, under the National Wildlife Refuge System, and ERCA, respectively. The conservation efforts have involved more than 200 community, governmental, NGO, and business partners (Hartig et al. 2010).

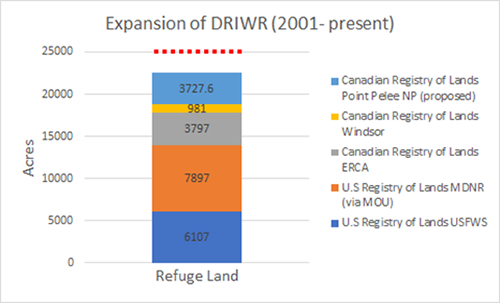

The DRIWR’s binational goal is to achieve a cumulative 25,000 acres (10,117.1 ha) of conserved lands, wetlands, and waters that are devoted to conservation and outdoor recreation by 2025. Nearly seven million people live within a 45-minute drive of the refuge (Hartig and Wallace 2015). As seen in Figure 3, to date, 3,797 acres (1,536.6 ha) of Essex Region Conservation Authority lands and 981 acres (397 ha) of City of Windsor lands have been added to a Canadian registry of lands for the refuge, and 7,897 acres (3,195.8 ha) of Michigan Department of Natural Resources lands have been added to a U.S. registry of lands that already includes 6,107 acres (2,471.4) ha of lands owned and/or cooperatively managed by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Together, the U.S. and Canada have 18,782 acres (7600.8 ha) of land in southwest Ontario and southeast Michigan being managed collaboratively under the DRIWR. Approximately 6,200 acres will have to be added to reach the binational goal of 25,000 acres by 2025.

Figure 3. Growth of the DRIWR from 2001 to present day. The red-dotted line indicated the binational goal of conserving 25,000 acres by 2025. Note that the 3,727.6 acres conserved through the Canadian Registry of Lands at Point Pelee NP is proposed.

Management Next Steps

To achieve the binational goal of conserving 25,000 acres (10,117.1 ha) as part of the DRIWR by 2025, it will be important for managers to collaborate on transboundary conservation and invest time and resources into building effective public-private partnerships. On the Canadian side a priority should be placed on adding Point Pelee National Park and The Nature Conservancy of Canada lands on Pelee Island to the Canadian registry of lands. Other Canadian lands to be explored for possible addition to the Canadian registry of lands include Mans Marsh, Fighting Island, and Jack Miner Bird Sanctuary. Possible cooperative agreements or acquisitions on the U.S. side include the West Marsh located adjacent to the Refuge’s Ford Marsh in Monroe County and Promedica property on the lower River Raisin in Monroe. Conservation easements should also be explored to build these registries of lands.

The DRIWR is still relatively new and has limited staff, so resources should be aimed at expanding the organizational capacity through the International Wildlife Refuge Alliance, the official Friends group of the DRIWR. Managers on both sides should continue to strengthen relationships with nongovernmental organizations like Metro Detroit Nature Network, the two hawk watches, Essex County Field Naturalists, etc.

Research/Monitoring Needs

Partners in the DRIWR understand that in order to sustain effective transboundary conservation, sound science must continue to be a priority (Hartig et al. 2010). Monitoring programs should be strengthened. Investments in citizen science initiatives that inform and guide management should be increased. Continued emphasis must be placed on adaptive management processes that analyze problems, seeks opportunities, outlines priorities, and engages actions in an iterative manner for continuous improvement (Hartig et al. 2010, Hartig 1997).

Good examples of integrating monitoring and research programs with management include fish spawning reef construction in the Detroit River, Detroit River-Western Lake Erie Cooperative Weed Management Area, Detroit River Area of Concern habitat restoration projects on both sides of the border, common tern habitat restoration, and wetland restoration efforts in both southwest Ontario and southeast Michigan. Continued priority should be placed on such efforts that strengthen the science-policy linkages. Finally, DRIWR monitoring and management must co-evolve with the Lake Erie Millennium Network, the Lake Erie Lakewide Action Management Plan, biennial State of the Strait Conferences, the Detroit River, Rouge River, and River Raisin Remedial Action Plans, the Lake Erie Committee of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, the Lake Erie Lakewide Management Plan, and others.

References

- EC and EPA (Environment Canada & U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1988. Upper Great Lakes connecting channels study. Final report, Volume II. U.S. Env. Protect Agency, Chicago, Ill. 591 pp.

- Hartig, J.H.; Wallace, M.C. Creating World-Class Gathering Places for People and Wildlife along the Detroit Riverfront, Michigan, USA. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15073–15098.

- Hartig, J.H. Bringing Conservation to Cities: Lessons from Building the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge; Ecovision World Monograph Series; Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management Society: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2014.

- Hartig, J.H.; Robinson, R.S.; Zarull, M.A. Designing a Sustainable Future through Creation of North America’s only International Wildlife Refuge. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3110–3128.

- Hartig, J.H. Great Lakes remedial action plans: Fostering adaptive ecosystem-based management processes. Amer. Rev. Can. Stud. 1997, 27, 437-458.

- Hartig, J. H. and Thomas R. L., 1988. Development of plans to restore degraded areas in the Great Lakes. Env. Managem. 12: 327–347.

- Manny, B.A., and Kenaga, D., 1991, The Detroit River— Effects of contaminants and human activities on aquatic plants and animals and their habitats: Hydrobiologia, v. 219, p. 269–279.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (U.S. FWS). 2005. Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment. pp. 1-65.

Contact Information regarding Growth of the the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge

John Hartig

University of Windsor, Great Lakes Institute for Environmental ResearchE-mail: jhhartig@uwindsor.ca

Collin Knauss

University of Michigan - School for Environment and SustainabilityE-mail: crknauss@umich.edu